In the bustling world of B2B operations, every decision, no matter how small, can ripple across supply chains, influence public perception, and impact the bottom line. Consider the humble drinking straw. For decades, it was a ubiquitous, unremarkable item. Yet, in recent years, it has become an unlikely flashpoint in the global sustainability debate, raising a critical question for procurement managers, operations directors, sustainability officers, and supply chain executives: are straws truly a significant environmental threat, or have they become a symbolic distraction from larger issues? The answer, while nuanced, carries profound implications for your corporate sustainability strategy, regulatory compliance, and brand reputation. Ignoring this seemingly minor item can expose your business to escalating reputational damage, missed market opportunities, and the operational complexities of a rapidly evolving regulatory landscape.

The scale of the problem is undeniable. Estimates suggest Americans alone use between 172 and 500 million plastic straws daily. Globally, this contributes to the approximately 8 million tons of plastic waste entering the world’s oceans each year. While plastic straws constitute a relatively small percentage (0.025% to 0.03%) of total ocean plastic waste, their visibility and persistence have made them a potent symbol of single-use plastic pollution. This isn’t merely an environmental concern; it’s a commercial imperative. Businesses that fail to adapt risk falling behind competitors who are proactively embracing sustainable practices, alienating environmentally conscious customers, and facing increasing scrutiny from regulators.

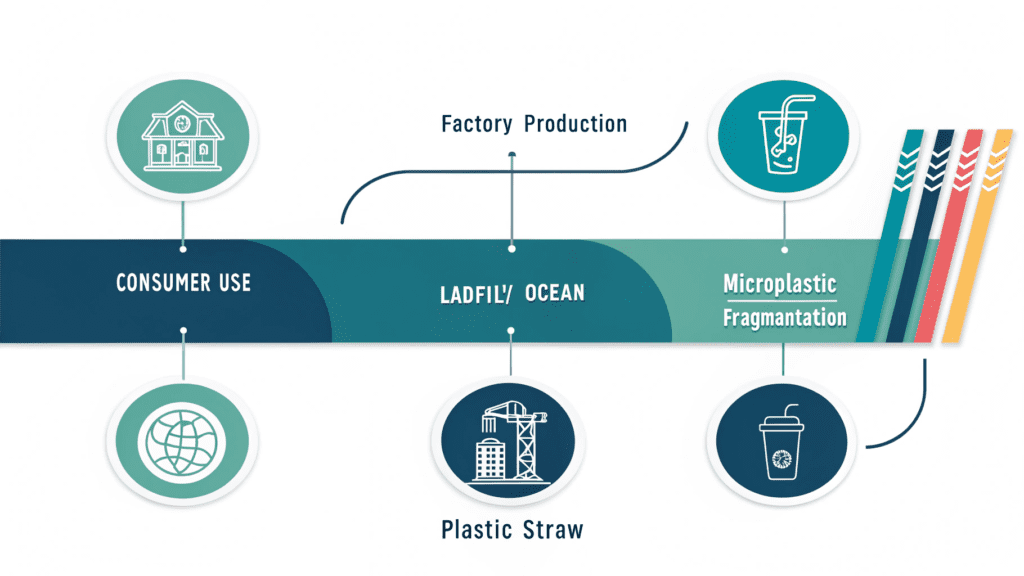

The journey of a plastic straw from production to landfill or ocean reveals a complex tapestry of environmental and social challenges. Manufactured primarily from polypropylene, a petroleum byproduct, their creation consumes significant natural resources and contributes to fossil fuel consumption and carbon emissions. Once used, these non-biodegradable items persist for hundreds of years. Rather than decomposing, they fragment into smaller and smaller pieces known as microplastics. These insidious particles, nearly impossible to remove, infiltrate water systems, soil, and even the food chain, ultimately being consumed by both animals and humans. The devastating impact on marine life is well-documented: plastic has been found in an estimated 90% of all seabirds and all sea turtle species, affecting around 800 marine species and killing at least 100,000 marine mammals annually. Furthermore, as plastics break down, they can release harmful chemicals like BPA and PFAS into the environment, posing additional risks.

The public outcry against plastic straws reached a fever pitch with viral moments, most notably a 2015 video depicting the removal of a plastic straw from a sea turtle’s nostril. This emotional catalyst spurred widespread corporate pledges and city-level bans, from Seattle (2018) and California (2019) to broader directives across the European Union, which saw 36.4 billion disposable straws discarded annually before stricter regulations. However, the narrative isn’t monolithic. Critics argue that focusing disproportionately on straws distracts from larger sources of pollution, such as fishing gear. Moreover, the effectiveness of bans is debated, especially when alternatives fail to meet consumer expectations, leading to frustration, as often seen with paper straws that become soggy or impart an undesirable taste.

Crucially, the debate around plastic straws also encompasses a vital social dimension: accessibility and inclusivity. For many individuals with physical disabilities, plastic straws are not a luxury but a necessary tool for independent drinking, offering flexibility and safety that rigid alternatives cannot. Metal or glass straws, while reusable, can pose risks of injury, while some paper straws may degrade too quickly or cause allergic reactions. The imposition of blanket bans without accessible alternatives places an undue burden on this community, highlighting the need for a nuanced approach that balances environmental goals with social responsibility. Businesses must navigate this complex landscape, ensuring their sustainability initiatives are both impactful and equitable. Understanding proper disposal methods for different types of alternatives is also key to ensuring true environmental benefit; for instance, a comprehensive guide on compostable straw disposal in hospitality settings can be found at Compostable Straw Disposal Guide.

For forward-thinking businesses, the imperative is not merely to react to bans but to strategically shift towards sustainable straw solutions that align with both environmental stewardship and operational realities. This involves a comprehensive understanding of the diverse alternatives available and their implications for cost, customer experience, and environmental footprint.

Diverse Paths to Sustainability: A Closer Look at Alternatives

The market has responded with a proliferation of options, broadly categorized into reusable and single-use biodegradable solutions:

Reusable Straws:

Ideal for controlled environments or customers seeking long-term sustainability.

- Metal straws (e.g., stainless steel, copper): Highly durable and easy to clean, they offer longevity but can feel hard, conduct temperature, and pose potential risks for individuals with limited motor control.

- Glass straws: Elegant and reusable, made from high-quality, shatter-resistant glass. They provide a premium experience but are more fragile than metal.

- Bamboo straws: Naturally sustainable and biodegradable, bamboo offers a rustic appeal. However, they can split or crack and require thorough cleaning to prevent mold.

- Silicone straws: Flexible, durable, and safe for children, these are excellent reusable options. Their pliability makes them a safer choice for many, including those with disabilities.

Single-Use Eco-Friendly Innovations:

Catering to convenience while minimizing environmental harm.

- Paper straws: A modernized version of the original 1888 invention, these are biodegradable and can break down in less than three months. However, concerns about durability (sogginess), potential paper aftertaste, and whether all types are truly biodegradable (some are wax- or plastic-coated) persist.

- Plant-based biodegradable straws: An expanding category made from materials like Polylactic Acid (PLA), Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA), sugarcane fibers, rice, pasta, seaweed, grass, coffee grounds, and coconut leaves. These aim to reduce carbon footprint, though some PLA options require specific industrial composting facilities. For a deeper dive into these options, explore Biodegradable Plastic Straws B2B Sustainability.

- “Straw straws”: Made from hollow grain stalks, these represent a completely natural and highly biodegradable single-use option.

To aid in this complex decision, procurement teams and operations managers can leverage a comprehensive comparison matrix:

| Straw Type | Cost-Effectiveness | Durability & Customer Experience | Disposal/Compostability | Environmental Footprint | Accessibility Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plastic | Very Low | High | Landfill/Ocean | High | High |

| Paper | Moderate | Low (can become soggy) | Biodegradable (variable) | Moderate | Variable |

| PLA | Moderate | Moderate (can soften) | Industrial Compost | Lower (plant-based) | High |

| Metal | High (initial investment) | High | Reusable | Low (with frequent reuse) | Low (rigid, temperature) |

| Silicone | High (initial investment) | High (flexible, safe) | Reusable | Low (with frequent reuse) | High |

| Bamboo | Moderate | Moderate (can split/crack) | Compostable | Low | Variable |

| Rice/Pasta/Seaweed | Moderate | Variable (softens quickly) | Edible/Compostable | Very Low | Variable |

This table underscores that while plastic offers low initial cost and high durability, its environmental and reputational costs are escalating. The ideal choice for a business often involves a hybrid approach, considering specific use cases, customer demographics, and local waste management infrastructure. For instance, a quick-service restaurant might opt for plant-based single-use options, while a high-end bar might invest in reusable metal or glass straws for dine-in service. Understanding storage guidelines for compostable straws is also crucial for maintaining their integrity and performance, details of which can be found at Compostable Straws Storage Guide.

The shift towards sustainable straws is not just a trend; it’s a fundamental market transformation. The global eco-friendly straws market, estimated at $1.5 billion in 2025, is projected to grow to approximately $2.8 billion by 2033, demonstrating an impressive compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 8%. This growth is fueled by both increasing consumer awareness and stringent government regulations. Major players in the foodservice industry, including Starbucks, McDonald’s, and Bon Appétit Management, have already committed to phasing out plastic straws, setting a precedent for the wider market. Cities like Seattle and nations such as France and the UK have implemented plastic straw bans or “straw upon request” policies, making regulatory compliance a non-negotiable aspect of operations in many key markets.

Innovation is driving this adoption, with advancements in material science creating new solutions like limestone-based straws (Biodolomer), bacterial cellulose, and seaweed straws. PHA (Polyhydroxyalkanoates) is particularly promising due to its ability to decompose in various environments, including marine settings, addressing critical limitations of earlier biodegradable options. For businesses, this means navigating new supply chain complexities – from sourcing novel materials to ensuring proper end-of-life disposal, whether through industrial composting or innovative recycling programs. Embracing these alternatives isn’t just about avoiding penalties; it’s about aligning with evolving consumer values, enhancing brand value, and securing a competitive edge in a market that increasingly prioritizes sustainability. Leading organizations are not just reacting but shaping the future of responsible consumption, understanding that proactive environmental stewardship attracts conscious consumers and mitigates long-term regulatory and reputational risks.

The debate around plastic straws, far from being a mere symbolic gesture, represents a microcosm of the larger sustainability challenges facing modern businesses. For procurement managers, operations directors, sustainability officers, and supply chain executives, it’s an urgent call to action. Moving beyond reactive compliance, your organization has the opportunity to develop a comprehensive sustainability strategy that not only addresses single-use plastics but also enhances brand loyalty, reduces operational risks, and unlocks new market share opportunities.

By evaluating your current straw usage and exploring viable eco-friendly alternatives, you can make informed decisions that benefit both your bottom line and the planet. Consult with industry experts and sustainable suppliers to tailor a strategy that aligns with your specific business needs, customer base, and long-term environmental commitments. The time to act is now. Embrace sustainable straw solutions to mitigate future regulatory risks, enhance your brand’s reputation, and secure a competitive edge in an increasingly environmentally conscious global market. This commitment can save your business significant compliance costs, insulate it from negative public sentiment, and position it as a leader in corporate social responsibility, potentially boosting market share in a rapidly growing eco-conscious economy.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1

While plastic straws constitute a small percentage (≈0.025%–0.03%) of total ocean plastic, their widespread use (≈172–500 million daily in the U.S.) and non-biodegradable nature mean they persist for centuries and fragment into harmful microplastics.

They contribute to ~8 million tons of plastic entering oceans annually, affect ≈800 marine species, and are linked to ≥100,000 marine mammal deaths per year. Production also consumes fossil fuels and emits CO₂.

Q2

Plastic straws add to microplastic pollution across water systems, soil, and the food chain. They harm marine life via ingestion and entanglement, consume resources and emit carbon during production, are hard to recycle, and frequently end up as landfill or litter.

Q3

Many people with disabilities rely on plastic straws for safe, independent drinking; alternatives may be unsuitable or risky.

For businesses, bans require compliance changes and new procurement, and can frustrate customers if alternatives perform poorly. Not adapting, however, risks penalties, reputational damage, and lost market opportunities.

Q4

Reusable options: stainless steel, glass, bamboo, silicone. Single-use compostable/biodegradable: paper, PLA, PHA, sugarcane, rice, pasta, seaweed, and hollow grain “straw straws.”

The best choice depends on specific use cases, customer needs, and disposal capabilities.

Q5

The eco-friendly straw market is undergoing rapid transformation: projected to grow from ~$1.5B in 2025 to ~$2.8B by 2033 (~8% CAGR), driven by regulation and consumer demand.

Innovations include PHA, limestone-based, bacterial cellulose, and seaweed straws aiming for higher performance and universal biodegradability. Major foodservice brands are already transitioning away from plastic.